The midden

HISTORY, PLACE, STORIES

Elle in front and Ela behind the midden framework.

By Dan Mahoney

By using community-based social arts practice in order to visualize connections between coastal people and place, Jenny Rock '93, Elle Gilchrist MPhil '21, and Ela Keegan '21 are working in New Zealand to document coastal heritage and visualize coastal futures under climate change.

COMPLEXITY

DAN MAHONEY: This project is one spoke of a larger project about the resilience of coastal communities living under the threat of climate change.

JENNY ROCK: That's right. We started in one of the southernmost communities in the world, a place called Stewart Island/Rakiura. There are about 400 people living there and they are pretty cut off from the rest of New Zealand. Although some would say they're not so cut off. They have a ferry and a little plane, but it costs a lot to get there. Electricity is all but impossible to afford. So, they have a lot of constraints, which makes for an amazing community. There have been waves of settling, including by Māori, and they're now kind of at the bottom end of the pack because of power issues, but even with these struggles, it's probably going to be a super resilient place in terms of climate change adaptability.

DAN: What is the nature of your project?

ELA KEEGAN: We are engaging communities using social arts practice. The center of our practice with this community was a printmaking workshop. We were making prints with the community, but there were many different phases before and after that too. In prepping ideas for images to make into printing plates, we were trying to understand what people's connection to coast was, and then we used that information to create different printing plates we brought into the workshop. It was like...

ELLE GILCHRIST: [Elle and Ela showing pictures simultaneously] Show and tell.

ELA: Show and tell... Here is the mooring field that is visible from the town.

The mooring field.

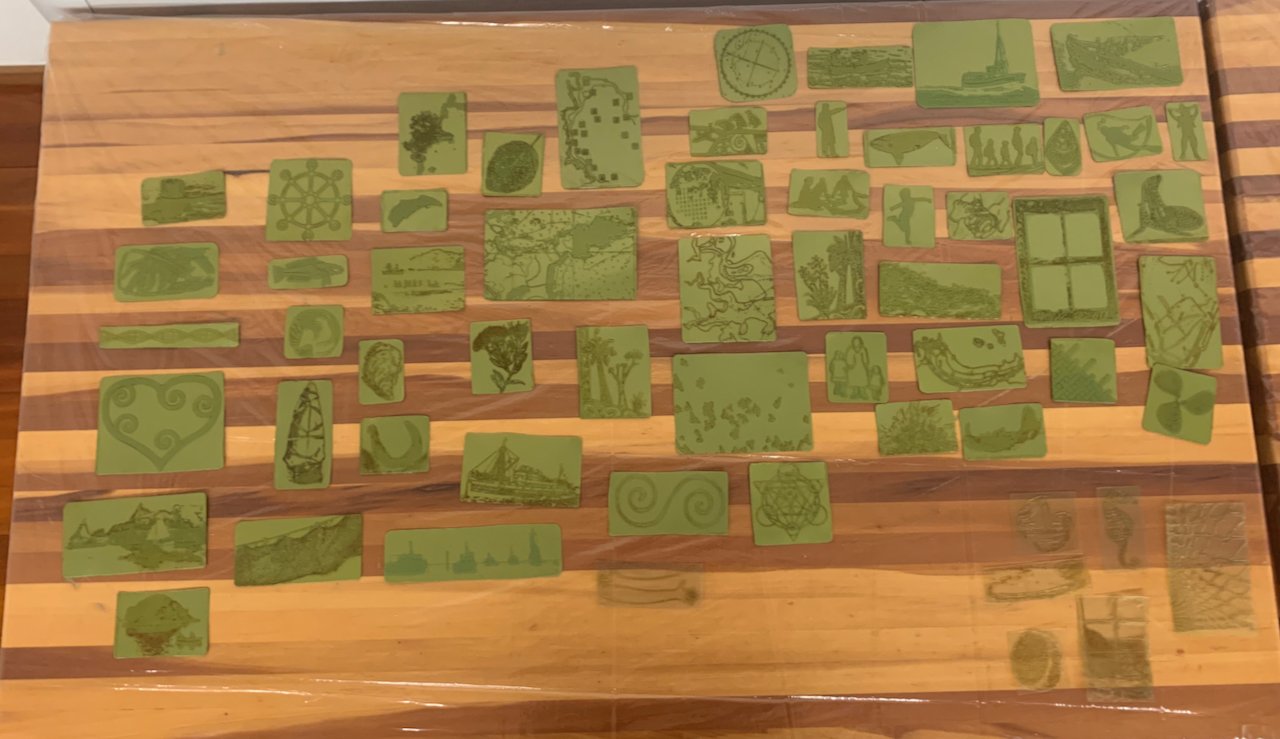

The image research side of the project took a few months to prepare. We used pictures the schoolkids made, we also researched archives to locate historical images we then turned into plates for printmaking. In the workshop itself, we asked people to create a print artifact that represented their connection to coast. What that then became was a community collaborative artwork that took the structure of a midden.

JENNY: The community was making choices as to what to include.

ELLE: Right. We started working through this idea of a midden because it's just such a cool metaphor. We're having people make these artifacts that represent their personal or their collective relationship to coast, but we're situating them visually within a midden structure. And there's something cool about that because a lot of this is thinking through heritage and what it means to basically exist in a place. How a community layers through time, and how each one of our own experiences of coast and of heritage is so multifaceted.

JENNY: And that's where the sea level stuff comes in because erosion and sea level rise is some of what will affect the continuance of the physical symbolism in terms of the heritage. Reckoning with that caused us to consider more questions: What kind of choices need to be made? What kind of actions are entailed in maintaining these things into the future?

DAN: Was it a challenge to integrate all those different people with different agendas into a coherent midden structure?

ELLE: No. It's such a different mindset than the US.

JENNY: It's probably even a different mindset than the North Island (of New Zealand). This is a much longer conversation, but for the sake of time, for various reasons, there was a lot of integration on Rakiura over the last few hundred years. In the South of New Zealand this was pretty intentional by Māori—to be inclusive. And there are a lot of reasons behind that. But it persists and it has made a very different place than say the North Island in terms of integration, and on Rakiura a very different resilience story.

Closeup of the midden.

ELLE: Right. And if you keep thinking about the midden, it's like that's the context upon which everything is standing on. That is the foundation. The history of all those years of that style of integration is the thing that frames the choices being made daily.

DAN: Interesting that these folks embrace the polyphony, many voices instead of just one or two.

JENNY: It's a bit political but, if asked, people are much more likely to name the diversity of their heritage rather than just pick one aspect of their heritage and run with that.

ELA: There were several people at the workshop who had come to the island—or weren't even from New Zealand originally—and were so aware of that heritage and held that kind of respect and care and importance of the heritage even though it wasn't necessarily their own... but it was theirs too because they were now living in this place. You could not be outside of it because as soon as you were living there you were absorbed by this heritage and that also informs this resilience.

ELLE: Yes, absolutely.

JENNY: There are lots of resources in Rakiura that have been capitalized on, and they've been capitalized on by different cultures, but the artifacts of those cultures are still cherished in a way... So, the heritage is cherished, and the naming of the places is reflective of all that. It's so...

ELA: Concentrated.

JENNY: Yes. And alive.

ELLE: It seems like the way that they draw their boundary of a group is like the island itself. It's not necessarily your genetic heritage, but more if you're living on Rakiura, you're part of that community. That's how I perceive it.

PROXIMITY

DAN: Rakiura sounds a lot like some corners of Maine I know where you only gain Mainer status after three generations.

JENNY: You do need to do a little time on Rakiura to get some cred, but it is more inclusive. Its extra-remote islandness demands it.

ELLE: In our work we found these qualities of place that shaped a lot of the socio-cultural dynamics were things like abundance and biodiversity...

ELA: And proximity.

ELLE: Proximity, right, and then isolation. Isolation from the mainland and the intense body of water that makes for difficult crossings. This helps create an intense local proximity, a closeness of the community which then contributes to a lot of self-reliance and adaptive qualities—like being opportunistic and intentional with resources. That sort of thinking blossoms out there.

JENNY: We worked a lot with the school trying to absorb as much as we could about what the young people valued, alongside the wider community’s heritage values, their sense-of-place values, and what they thought needed protection to carry on... but there was also fear, like folks saying we're good for now, but we don't know how much longer we can carry on (i.e., How long can we maintain this level of necessary community activity and leadership?).

ELLE: We went back and forth from the school to the community, sponging up what the printing plates needed to have in them to capture the complexity and nuances of what it means to be in this place.

JENNY: We used printmaking as a social arts practice. Printmaking is nonconfrontational, anyone can do it, and when you are printing you create multiple images with multiple combinations and from all that a story emerges. We were very intentional in our workshops to allow for participants to play while thinking hard about their perspective and how to encapsulate that visually. All in all, we offered up 80 printing plates. Imagine that, and the complexity when you start having multiple plates printed together.

DAN: Who made all these plates?

JENNY: Raise your hand if you made plates. [They all raise their hands.] I use printmaking for a lot of community projects as a different form of community consultation. You can think about things while your hands are busy. It gives you time to reflect before you speak and to do so in a social mix where you are exposed to other’s perceptions, too. It also attracts different people than those who might usually come and be vocal at a town meeting. It's as easy as making choices, and family groups can even work on a piece together.

ELLE: It’s fun too—all the different color choices.

JENNY: We bring this big press down—it kind of looks like the wheel on a ship—which makes it appealing for all ages and walks of life.

DAN: I love old presses... You're looking at technology that was built in the 19th century that is still functioning today. So cool. So now you have all this stuff created by the community, but so what? What now?

ELA: I'm here doing my master's thesis and Jenny is my advisor. I'm deep diving into these artifacts the community created, analyzing the images people decided to put together, how they were used, and what values they stand for. I'm also analyzing the story captures, looking at the narratives about why people made the prints they did, the narratives about their relationship to coast, what practices they want to continue in the future, and looking to understand the threads of resilience that exist in the community.

ELLE: Once we had the midden created, we brought the community together and had them respond to what they were seeing. We prompted some questions about navigating change in the future and what actions they needed to take to move forward. This facilitated the creation of this gigantic mind map which pointed to how the community defined resilience and the qualities of resilience they valued. The questions then became: What is it that people want to carry into the future? How do they hold onto the current qualities they value while making space for change?

ELA: What the community told us was this: They wanted to have a continuation of wisdom, knowledge, and history flowing through multiple generations. They wanted to continue the community culture that maintains safety and freedom, remarkably resilient youth, and a volunteering ethic. This was incredibly important to them: there is a strong history of volunteerism that shapes the tightness of the community that is being threatened by time, energy, the affordability of things, and growth.

JENNY: Gross growth.

ELLE: Gross growth. Right [laughter]. They also wanted the mindset of valuing their place and their resources and not taking things for granted. It's a very intangible heritage. Strategic community involvement and decision-making are directly related to preserving and protecting the environment as a provider. But they also struggle with external government issues, figuring out better ways to navigate external bodies of governance, the top-down structures that operate at a distance. All of this is related to strategic decision-making about material things like wharfs, schools, electricity, and the affordability of things.

DAN: That's a lot.

ELA: It is a lot. For me, writing my thesis, using all the notes and mind maps and complexity we've encountered… it's important for our work to represent the community’s experience and what the community actually wants.

Washing plates after UV light exposure.

Some of the many plates created from visual research.

VISIBILITY

DAN: The midden is a great structure to represent the complexity of a place. Was that always the plan, or how did that come into being?

JENNY: It shaped everything. The midden is in layers, so there is a temporal element, but it's also collectively a big mess of… well… stuff. But it's intentional stuff. A midden shows people’s actions and choices, it shows your habits and values. And with something as dramatic as climate change, we all start thinking of what we will lose from the past, but on Rakiura that temporal line, that heritage, is still held close; the past is still very much alive. The structure is a midden of the past but it's also a midden of the present and of the future. Articulating that for other communities to learn from is important, because community-to-community conversation is what, in the end, we are facilitating, and is a big challenge. One of the things that made this community so resilient was that active line which really acts like a circle. It's an embodied heritage that is really strong in spite of a lot of challenges, but maybe really strong because of those challenges.

DAN: So, Ela is doing her master's work there and Elle you have a master's already right?

ELLE: Yeah, I finished my master's at COA a year ago. I was looking at some of the socio-ecological dynamics of things that were happening in a fishing community in Yucatán. I was looking at the relationship with the ocean and how that webs out into everything else, in particular things like the growth of tourism and the decline of the grouper fishery. I took a multimethods approach. I was living in the community, doing a bunch of interviews, and some social art. We did really cool collages, which was a similar flavor of project to this one but with different media.

DAN: I keep hearing this term: social art practice. What is that and why is it important for this sort of work?

ELLE: Art is just really interesting... It's this thing we ooze sometimes. It's an expression of something that's in here [gestures to her body] and it does not need to be verbal although it could be verbal. We've been working in mediums that are very accessible—collage and printmaking are accessible and satisfying to work with, addictive even—which make them ideal for expressing ideas in a very physical way. You have to use your hands and your body to select things and think through ideas as you're creating, and it slows you down, which is nice. You can make thoughtful choices that we can then glean a lot of understanding from. It is also a less extractive method of coming to understand people and their stuff (perceptions, ideas, feelings) and the way they relate to their stuff.

ELA: It allows working with a community to be much more personal. When I was at COA, I did a lot of projects in the Mapping the Ocean’s Stories course (page 39) and getting to interview people. Then we took the audio and made either narrative or sound pieces. There was great creativity in that practice. There is something so powerful about letting people tell their own stories. It feels less intrusive as a researcher coming into a community and just trying to understand and learn instead of trying to take something. The social art practice just creates a channel for that dialogue to happen.

ELLE: And depending on how you work, different ideas emerge that might be hidden if you were just doing a verbal survey.

ELA: People were taking the artwork with them; when I would show up to do an interview for my thesis the art would already be on the fridge. It was already part of their home.

Jenny (left) and Elle (right) with the completed midden hanging in the Rakiura Museum.

DAN: I'm thinking of graffiti here, as in a record of a person being in a place or a map of being in several places.

JENNY: It all comes down to maps in the end, whether it's physical maps or mind maps or using a midden as a map of human activity. Another one of the mapping layers of this project was going to be using technology to geolocate values, but that is for a future stage. We are sitting on a huge amount of generated data that we are now sorting into some bigger messages of meaning about tangible and intangible values, values oftentimes missed by models that only address specific aspects of economic infrastructure or specific threats to X from Y or Z. So, for our work, if there is a way to at least map the data we've been gathering it's taking a first step in reaching the power brokers who need to widen their view because they tend to look at physical infrastructure being the only value that matters.

DAN: Do you see your primary function as reaching those power brokers and showing them what you are seeing in terms of how "value" works in these communities?

ELLE: It is important to be able to translate data to people who hold legislative power, but at the same time, there is a lot of power in community members being able to see for themselves, visually or even foundationally, in order to understand where these places of heritage are. If you have that knowledge of yourself and your community then there is a certain empowerment which leads to more agency in being able to make strategic decisions, and that can then guide your actions when you are working with legislation or with top-down power structures. So, yes, translation is important but it’s not the only valuable piece here.

JENNY: I remember what I wanted to talk about from earlier: wharfs.

DAN: That's a great word to remember.

JENNY: Wharfs are important. The wharf was such a huge metaphor down there for so many of the inherent issues, the power struggles, the growth stresses, the lived heritage, and the huge connection with place and the resilience of the community. Just a tiny example of what was unique to that place. When we began our work, we were thinking about islands and common features of islands, but in doing the work we kept coming back to the wharf. One of the things that the community expressed really strongly was that their children are very mature, and they are mature because they have huge freedom, and they have huge freedom because they have a community looking after them.

DAN: That strong community feature again.

JENNY: And it is so boat based. So, one of the freedoms is at something like age seven they go through the rite of passage where they can go out and row the dinghy, and then by eight or nine they can row the dinghy with a mate and no adult... And then they can go out to Big Rock and fish on their own. But all the rites of passage happen because there are people out there—not necessarily family members—keeping an eye on them. But that watchful eye needs to be there for the freedom to be there, so the community suffers when folks are overstressed with work or other commitments trying to make ends meet. And maybe someone from there or away comes up with an idea for the community to gain income by constructing an enormous new pier that can handle big cruise ships... But that enormous pier is not something a youngster can pop their little dinghy off of. You can see where this is going, right? One thing leads to another, and another, and another, but because they've articulated the value of the freedom and maturity of their children, those things become overtly in conflict. You know, Rakiura children do come back too, not always, but many times, and because of that the heritage and those memories are carried into the future. You mess with one structure like the wharf, and you've jeopardized all of that.

DAN: It seems so obvious but sometimes what is obvious is easiest to forget.

JENNY: The social art practice is really just a method of making space for people to think and realize and have social conversations around artmaking and images... It's empowerment through active realization, memory, and recognizing what's important, because it would be easy to lose sight of something so common and think, Okay, let's have a really big pier and only afterwards realize what you've lost. This practice helps center those things.

ELLE: Art helps bring out that sort of understanding...

ELA: Exactly. It's a process of understanding.